Apologies to your favorite delivery joint, but you should never eat a meal from one of those black plastic food containers again—because, as researchers recently revealed, black plastic can contain all kinds of harmful chemicals.

Last year, researchers at University of Plymouth published a study in Environment International reporting on the toxic material’s life cycle—the first time that much of the public had ever heard about the dangers of black plastic. The problem stems from the technology used in recycling centers. These systems have trouble seeing and sorting black plastics out from other plastics, which means a majority of black plastic that arrives at recycling centers actually goes into the trash instead of being turned into new products. “Most people assume black plastics get recycled like other plastics, but in reality black materials are not picked up at recycle centers by the normal infrared technology,” University of Plymouth’s Dr. Andrew Turner told me at the time. “Because we do not recycle black plastic in general, we seem to be turning to black e-waste as a source for black consumer products.”

The problem with reusing that plastic is that it’s often filled with lead and flame-retardant chemicals like bromine—the sort of stuff that is never meant to go on your skin or in your mouth. Ultimately, the plastic used in old electronics ends up mixed with old food-grade plastic. Suddenly, there are poisonous additives that exceed legal limits in our jewelry, coffee stirrers, Christmas decor, and garden hoses. Ongoing bromine exposure can give you systematic poisoning to the brain and kidneys. Lead can permanently hinder physical and mental development.

ONE MAN’S TRASH IS ANOTHER MAN’S TREASURE

“Basically black plastic is both a beautiful thing and an ugly thing,” says Alvin Orbaek White, a researcher at the Energy Safety Research Institute at Swansea University. “It’s beautiful that all plastic can become black plastic. It gives a pathway for plastic to be recycled. But it can’t be recycled after [because of current recycling tech]. It’s already gone to the end of the food chain. [And] the fact that it’s black hides all sorts of other stuff in there.”

White is part of a team of researchers developing ways to re-use old black plastics—which represent as much as 15% of all plastic waste. “We need to start looking at this material as a commodity,” he says. “It inherently lasts so long; that’s the problem with it. [But] that’s only because it’s so stable! So let’s take that stability to be a sign of its ability to be continuously used.”

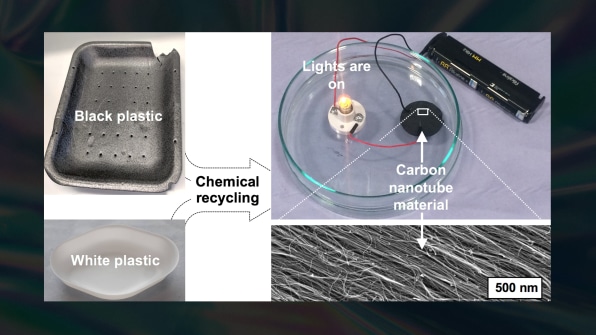

In the June issue of the Journal of Carbon Research, they describe how they discovered a way to turn black plastic waste into fully functional electrical wiring. Their new technique involves transforming the carbon in the plastic into carbon nanotubes, which are mini cylinders constructed from single-atom-thick carbon shells. They’re capable of all sorts of wondrous feats, like conducting electricity. Using similar techniques, he believes the method could also create carbon fiber, or graphene—the sorts of materials prized in places like the aerospace industry for their high strength and low weight.

The process begins with liquifying the plastic in a solvent. Then it’s placed into a 750-degree furnace with a form of iron (in the future, this iron could literally be provided in the form of rust, he says, since it’s so cheap and widespread) that serves as a catalyst for the reaction. In these conditions, the plastic grows into carbon nanotubes, capable of transporting electricity. It’s not the first time plastic has been turned into nanotubes, but the practical ease and flexibility of this process is the paper’s major discovery. White’s team proved it could conduct electricity by simply taking some of the wiring it created out of plastic and hooking it up to a light—which turned on.

“The stuff in the paper is straight off the baker’s rack, it doesn’t have the ice and sugar on it,” says White, who also founded a startup called Trimtabs to commercialize the technology, for which he is currently raising money. “It’s rough, but I wanted to show even though it comes out of the oven, it’s ready to go.”

He adds that the process is scalable today; it just requires chemical engineers to translate the science to industrial-sized machinery. Further research will explore more formulations of plastics that could be used, and work on refining the nanotubes to maximize performance (there are over 100 styles of nanotubes known to scientists with different properties, and the wiring built in this research is a mix of many types).

Once White gets going, he paints a tantalizing future for all this dangerous black plastic waste. His method for creating nanotubes isn’t precious; it’s adaptable to inherently impure plastics by design, so it’s scalable globally with local recycling streams, no matter what sorts of impurities might be in the mix. As for potential environmental impact of recycling plastics with all sorts of impurities, any carbon components in the plastic would just make their way into the nanotube structure. Any heavy metals, like lead, would burn away and be captured by the oven’s HEPA filters.

“I’m employing the Hippocratic Oath in this work, too,” says White of the environmental impact. “I plan to do no harm.”

THE INFRASTRUCTURE OF THE FUTURE?

As for the practical impact of plastic-based wiring, most wiring today is built from copper, a finite resource, which is a superb conductor of electricity, but also quite heavy and generates a lot of heat in the process of transporting energy—so much so that it actually slowly stretches and melts over time.

White’s recycled carbon nano wiring is a bit less efficient at moving power today, but it runs completely cool, is more flexible, and is far lighter. That means it could be a superior, immediate option for weight-restrictive applications like aerospace engineering, where nanotubes would be a better alternative for powering many flight instruments. It could also allow more, and longer, stretches of infrastructural wiring to be buried, since underground copper wiring can actually overheat and slowly melt itself without active cooling systems, which is a big reason why we rely on so many above ground pylons today.

Whether or not White’s venture succeeds, his ongoing research demonstrates an important truth: That while we’re buried in toxic black plastic waste today, it’s entirely possible to discover new ways to turn this waste into future-forward materials capable of benefiting our lives in all sorts of ways. We really can dig ourselves out of this trash heap. And our world will be better once we do.